I accidentally wrote a cookbook

The Sunday Times called me ‘the high priestess of fir related snacking.’ What in Santa’s bollocks was going on? How had I become Christmas Tree Girl?

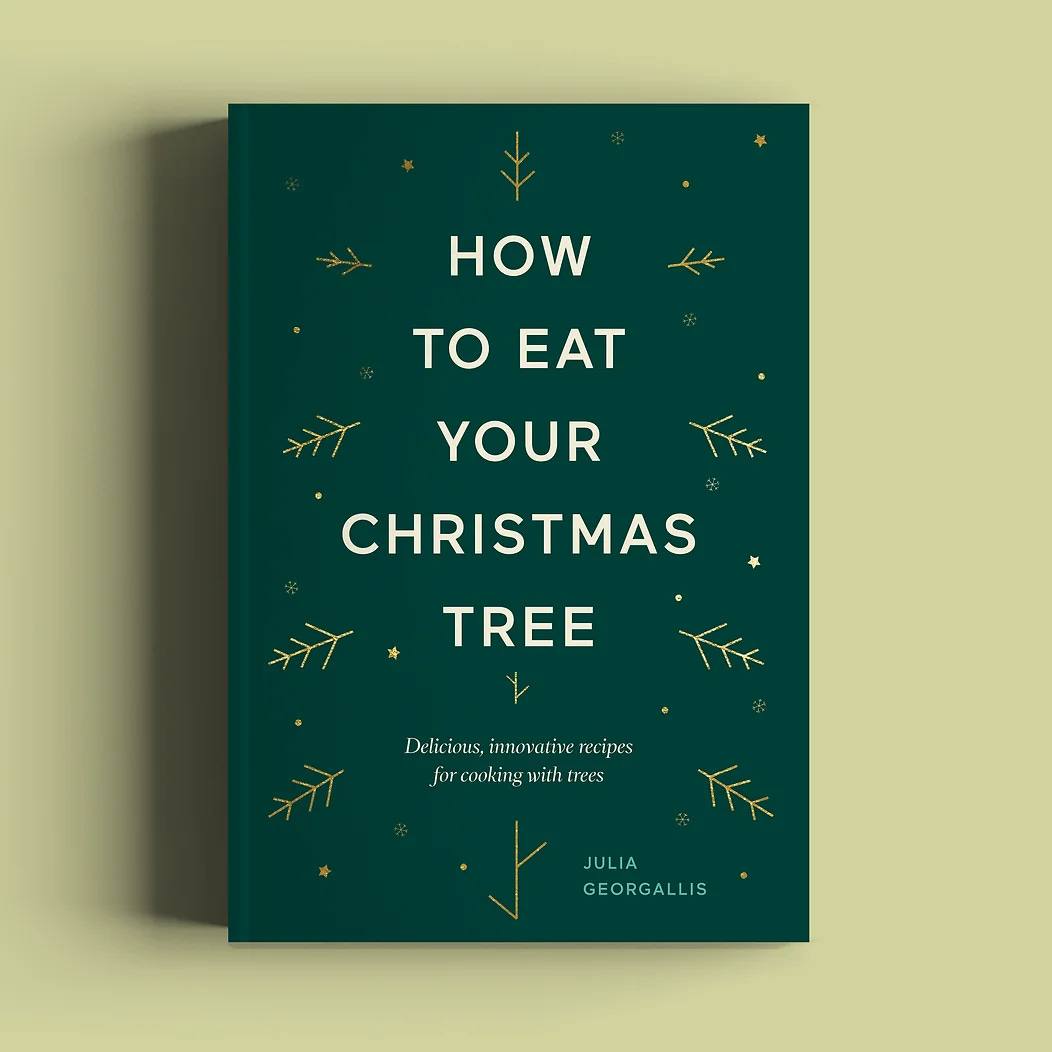

In the winter of 2019, I self published a little, green cookbook called ‘How to eat your Christmas tree.’ It was a light-hearted, no frills, paperback print, more zine than cookbook, with a handful of recipes about cooking with trees and thoughts on sustainability around the festive season. Shortly after its release, it was picked up by publisher Hardie Grant, re-written and re-released the following year slap bang in the middle of Covid. After that, it took off in a way that I hadn’t anticipated and was, quite honestly, not prepared for because I hadn’t really written the book very consciously.

Writing it was actually a bit of an accident.

Please don’t send me to jail for talking about Christmas when the leaves have barely changed colour, but I’d like to share the story of how I wrote my cookbook with you because it’s a bit of a weird one and not the usual route into publishing. Perhaps it will help if you’re trying to do the same.

Up to the point of putting pen to paper, I had run a series of supper clubs called ‘How to eat your Christmas tree’ since 2015, which I started with friend and designer Lauren Davies shortly after I had made the decision to quit design and retrain as a baker. Lauren and I were both quite into scrappy cooking (cooking with leftovers, not wasting anything, foraging, etc etc.). We thought, perhaps, we’d run a supper club together around Christmas time and asked ourselves what was thrown away the most around that time of year that might be edible to encourage discussion around waste? A little lightbulb floated over our heads — it was Christmas trees, wasn’t it? People fucking loved Christmas trees.

In 2015, this was the extent of what sustainability was to me — leftovers, waste, recycling. I understand now that it is much bigger than that, that there needs to be radical, systematic shifts in all aspects of life to achieve any semblance of sustainable living, but just ten years ago the noises surrounding climate crisis were pitched to a low hum, not nearly as loud or as urgent as they are now. Cooking with Christmas trees was how we were going to save the polar bears, apparently (spoiler, it wasn’t and we didn’t).

Just a year before the Brexit referendum (when the arse seemingly fell out of the UK), life was cheaper and many more people seemed to have expendable income to go to all the workshops and the supper clubs and the odd, niche events that London had to offer — Lauren and I dived feet first into cooking with Christmas trees and we launched three dates for a supper club series where we would serve the bonkers things we made from our experiments. We drove around the edges of the M25 looking for trees to eat and ransacked the good people of North London’s gardens. Apart from my early rudimentary bakery training, neither of us had much experience in hospitality and we made some horrible dishes at first (which we didn’t serve obvs). Bless the people who bought tickets to our dinners and trusted us with their digestive systems.

But anyway, we cracked on and our project turned out very nicely — I was proud of the things that we made in that first year and Lauren and I had a lot of fun cooking together. Not that press is the yard stick of good cooking but we were in Time Out, Vice and Mold. Plus, the Daily Mail wrote a weird article about us and we somehow ended up on ITV’s 6 o’clock news. So we did, in the end, manage to launch a discussion that people are still having today — in times of environmental decline where trees are some of our most important allies in the fight to remedy the climate crisis, why the fuck are we still cutting down thousands of them a year to hold hostage in our living rooms between December and January?

The following year, Lauren made the decision to stick to design (and has since had a very colourful and successful career!) and I decided to stick to hospitality, so I continued to run the supper clubs each Christmas by myself. I added more dishes to the project and continued to be involved with discussions around festive sustainability. But then, in 2018, I had a monumental, slightly-earlier-than-usual-mid-life crisis. I decided to radically shake up my life — I finally got a diagnosis for all the odd symptoms I had always suffered with (I have ankylosing spondylitis), I started therapy and, less sensibly, instead of putting my savings into a house deposit or expanding my business, I disappeared and travelled through Brazil, California and Southern Europe before settling in Lisbon in October 2018. For the first few months in Portugal, I lived off my (dwindling) savings and would travel back to London every few weeks to do a bit of freelance work. It wasn’t a practical way to live but, for the first time in my life I had time and space to myself. With this new life, I felt the need to leave behind some of my previous work so I decided it would be nice to bookend the Christmas tree project with a collection of recipes and thoughts from the last few years of cooking with trees. Though I worked hard on it, I didn’t care about how popular it would be, I didn’t care about sales, I didn’t care about what people thought of it. I just wanted a well-executed, neat conclusion.

I spent winter and spring planning and designing the book and a long, hot Portuguese summer writing and cooking. When I didn’t know how to do something, I asked for help from people who knew more than I did and I fronted the money for the book myself but earned it back by making AN ABSOLUTELY AWFUL Kickstarter campaign (it was very cringe). If I were to self publish again, I would probably use a print-on-demand service instead as it means that the upfront costs of a cookbook/book/zine are lower. By the end of September, I had 300 little green guys printed and sent off to those who had supported the crowdfunding campaign. (P.S 300 is too many. Print less copies but do more print runs).

There we go, it was done, I could move on and do other things.

But what I thought would grant me closure actually ended up giving me expansion.

A month after launching the self published version, a publishing director at Hardie Grant slid into my DM’s asking questions about my book. She had seen it online through the photographer I had worked with, Lizzie Mayson, who did a lot of work for the publishing house. Though most things were done on the cheap, I really invested in the cookbook’s photography. This paid off not just because Lizzie’s work was (and is!) beautiful, but because she was well connected and, as she shared images of my book on her socials, my project got a lot of unexpected attention.

Unbelievably, I was so convinced that I didn’t want to progress the project any further that, initially, I turned down Hardie Grant’s offer. I was actually a bit of a dickhead about the entire contract — I think there was something about putting my work in someone else’s hands and releasing it into the wild that I felt suspicious and a little scared of. In the end, I signed on the dotted line and, though I didn’t anticipate that much would come from it, Hardie Grant ended up being fantastic to work with — working with a publisher made me feel protected and validated in a way that working on my own projects never had before.

However, I do still see the pros of self publishing, in particular now that publishing houses can’t offer as much money as they once did and now that there are a lot more tools and resources to go full indie. Another thing to note about working with publishers is that you do still have to do a lot of work yourself (not that there’s anything necessarily wrong with this, there’s no such thing as a free lunch), primarily press, which is something that many don’t realise when they sign cookbook deals.

Two months after signing, Covid was in full swing and I spent Lockdown Numero Uno by myself in my Lisbon apartment, re-writing parts of my book and adding recipes. The hardback, extended version was published in October 2020, as the world hurtled towards its first Covid Christmas. There was no fanfare, no big launch party, no book signings, no workshops or supper clubs to celebrate the publication because we were all stuck indoors trying not to die.

But it didn’t really matter in the end, because the book, much to my surprise, was publicised in almost every single major news publication in the UK, USA and Canada. Eventually it was translated into German and French and it also did pretty well in Italy. I was on podcasts, panel discussions, television, radio interviews. The Sunday Times called me ‘the high priestess of fir related snacking.’ What in Santa’s bollocks was going on? How had I become Christmas Tree Girl? It was and still is utterly ridiculous.

I still don’t really know why ‘How to eat your Christmas tree’ has been as successful as it has. Perhaps it hit upon a zeitgeist just as we were waking up to the terrifying idea of total climate obliteration and Christmas trees seemed like a manageable, not particularly scary thing to think about (if a little futile). But perhaps it was also because I wrote it in absolute earnest, without taking myself too seriously, which I find harder and harder to do these days.

Because I didn’t expect any eyes on the project, at first, I was painfully underprepared, under coached and very fucking awkward when dealing with the media. I messed up a good few interviews (I want the ground to swallow me up when I think about how poorly I answered questions next to Michael Rosen on BBC Radio 4’s Saturday Live) but I’ve gotten better at it over time. Every year in the weird, dead period between Christmas and New Year’s Eve, the press still come knocking — I have, somehow, become the unofficial spokesperson of what to do with a Christmas tree once Christmas is over.

As well as praise, I was trolled pretty hard. I received so many abusive emails (mainly from Americans) about my decision to cook with trees that I had to take down my website’s contact form. A surprisingly high number of people were worried about the abortive effects of conifers on pregnant women, because apparently cows abort their calves when they eat too many pine needles (must I remind everyone that cows are not women). Someone got VERY cross with me because they made a mess in their kitchen when trying to make Christmas tree powder (tough tits, I’m not beefing Nigella when I fuck up her meringue recipe). MANY MANY MANY PEOPLE told me to stick a Christmas tree up my arse. More publicly, I was trolled live on air by two hosts on TalkRADIO and by Bradley Walsh on Radio 4 (much to the displeasure of the listeners who wrote in to complain, which I felt quite smug about). I did enjoy it, though, when my project was poked at by Actual Funny Person, Sandy Toksvig. I am very much anticipating more grief this coming winter after the Belgian government released a warning about eating trees last Christmas (it felt like a personal attack), but though previous bad press has made me want to retreat and never do anything in the public eye ever again, I’ve reverted to the original, playful spirit in which the project was started and the cookbook written and I’ve stopped taking it all so seriously again — come at me, Belgium.

I still don’t think we shouldn’t be keeping Christmas trees at all, though.

‘How to eat your Christmas tree’ has, quite by accident, changed the direction of my career. Not that I’m a wildly successful writer or journalist and the book hasn’t sold millions of copies (last time I checked, the sales figures were hovering around 15,000). But it doesn’t really matter, because it has brought about monumental change in my own little world — I wouldn’t have become so interested in food systems or the environment and I certainly wouldn’t have had the opportunity to start writing professionally.

As well as contributing heavily to my own development, in the ten years since its inception, the project has also contributed to the, now global, debate about what to do with a Christmas tree post-Christmas and how we can be less wasteful during the festive period in general (I’m not sure it’s solved any problems necessarily, but it has got people talking, it has got eyes on the issues).

In short, ‘How to eat your Christmas tree’ has done a lot of work, both for me and for the wider public discourse surrounding waste.

And so, this coming winter, though I have a few events and articles about the book lined up, once those are wrapped up I think that I’m finally, actually, properly, really, really ready to give the project a well deserved rest.

You can follow the project here or on my socials to see if I actually manage it this time.

Another gem. I always feel like we are just sitting across the table and you’re telling me this story over some cake. Also, wth, how could anyone get angry or cross about a cookbook about eating Christmas trees? SMH.